It’s sad to see endless rows of dead olive trees, looking like the skeletons of elderly men and women. But these trees did not die of old age. They were killed by a bacterium, Xylella fastidiosa, which according to researchers hitched a ride on an ornamental plant from Costa Rica in 2010.

It was initially unclear why the trees were dying. When the cause was discovered to be Xylella fastidiosa, a bacterium never found in Europe before, a real shockwave passed through scientists, European politicians and above all olive growers, who saw their heritage and incomes threatened. A variant of the same bacterium had previously wreaked havoc in the vineyards of California and the citrus plantations of Brazil, causing damage amounting to billions of euros.

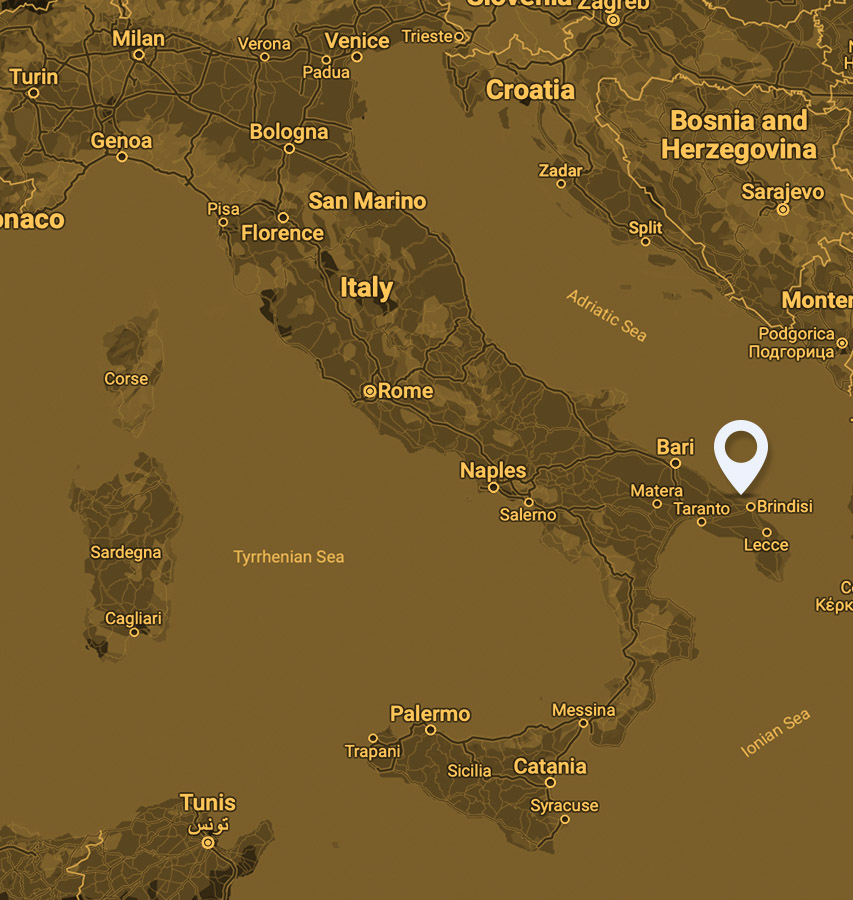

The Xylella fastidiosa bacterium, for which no remedy has yet been found, is spread from tree to tree by a tiny spittlebug that blocks the xylem, the vascular tissue that transports water from the roots to the branches, with the result that the trees dry out and die. Of the sixty million olive trees in the Apulia region, twenty million have already been infected and succumbed to desiccation.

Ulivi secolari

Among those sixty million olive trees in the Apulia region are half a million ‘ulivi secolari’, as the much-loved ancient olive trees, their bodies contorted by age, are known. Centuries old, these trees are of more than merely economic importance, since they form an important part of Italy’s cultural heritage and identity.

Xylella fastidiosa is not the only threat to the many thousands of small, independent producers of olive oil. The relentless growth in demand for olive oil has led to immense increases in scale and industrialization. Fifteen years ago, olives were grown in 46 countries; now the figure is 68. Every second, ten olive trees are planted somewhere in the world.

Economy and olive oil

Italy produces some 15 per cent of the world’s virgin olive oil, worth around two billion euro. Spain is an even bigger producer of olive oil, while Greece also makes a considerable contribution. Much is therefore at stake economically and the entire agricultural sector is threatened. In Puglia it is the small farmers and families who work their own olive groves whose livelihood is in danger.

Xylella fastidiosa and Covid

A comparison between the outbreak of Xylella fastidiosa and Covid-19 seems unavoidable, both in how it is combatted and how it can be prevented. True, there is not yet a vaccine against Xylella fastidiosa, but neither the bacterium nor Covid came by foot. Xylella fastidiosa hitched a ride on a plant from Costa Rica and both undoubtedly arrived by plane. Such is the price of globalization.

There are other similarities too. Both are extremely infectious; Xylella travels at 30 miles a year, by foot as yet, rather than plane. Strict measures need to be in place to prevent its spread. The persistent conspiracy theories doing the rounds present another parallel with Covid. When in 2010 the first symptoms were observed, people in Puglia did not know what was killing their trees. Three years later, scientists discovered that it was the Xylella bacterium. The Italian government introduced strict measures to prevent it from spreading, which came down to grubbing up trees. Sick trees must be felled and the wood burned.

That awakened intense emotions and provoked demonstrations. Owners chained themselves to their trees, demonstrated in city centres and won the support of TV personalities and public opinion. As with Covid and the resistance to lockdowns, disbelief and denial fuelled many conspiracy theories; ‘It was the agrochemicals industry that had caused the infection so that it could sell genetically modified seed to farmers, or the mafia, eager to use the land cleared of olive trees for speculation and construction. Or the Italian government, which needed the wood from the trees to keep its biomass power stations burning.’

Science and farmers’ wisdom

As with the Covid outbreak, the discovery of Xylella fastidiosa in Italian olive groves mobilized the entire scientific community to research this devastating bacterium. But farmers cannot simply wait until science has found a way to combat infection by this devastating bacterium.

Agronomists, farmers and scientists have joined forces to seek ways of preventing the infection from spreading and to save at least a few of the ulivi secolari. Hope-giving results emerged from the grafting of new, more resistant varieties onto old, sick trees. But alongside scientific research, farmers’ wisdom may be even more important in the battle against the bacterium. As with Covid, it all starts with resilience.

The 70-hectare olive grove is an extremely important part of his farm. It consists of very old Celina di Nardò and Ogliarola olive trees, planted 150 years ago on 30 hectares, and new intensive cultivation of Leccino, Frantoio, Cima di Melfi, Picholine, Toscanina, Simone and Pendolino olive trees, known for the intense and fruity taste of the oil they produce.

“This is an organic farm, which is to say that we use only natural fertilizers, no synthetic, petrochemical fertilizers, thereby sustaining the health of the soil and the ecosystem. The olives are picked directly from the tree in November and December, and processed quickly in order to avoid fermentation.”

It’s the resilience, stupid!

Meeting Antonello Bruno

Antonello is a lawyer and president of Confagricoltura Brindisi. He is also a grower of organic vegetables, tomatoes and fruit, and has 70 hectares of ancient olive trees. He tells his story standing in his olive grove in front of a 150-year-old tree infected by Xylella that he saved by grafting a new, more resistant variety onto it, and by using a resilient method of growing.

We have selected another two stories that might inspire you.